Or: How I think about the differences between a good drink and a great one.

My Definition of a Great Drink:

This seems like an easy question, admittedly — “the one that tastes awesome” — but there’s more to it than that. A great drink:

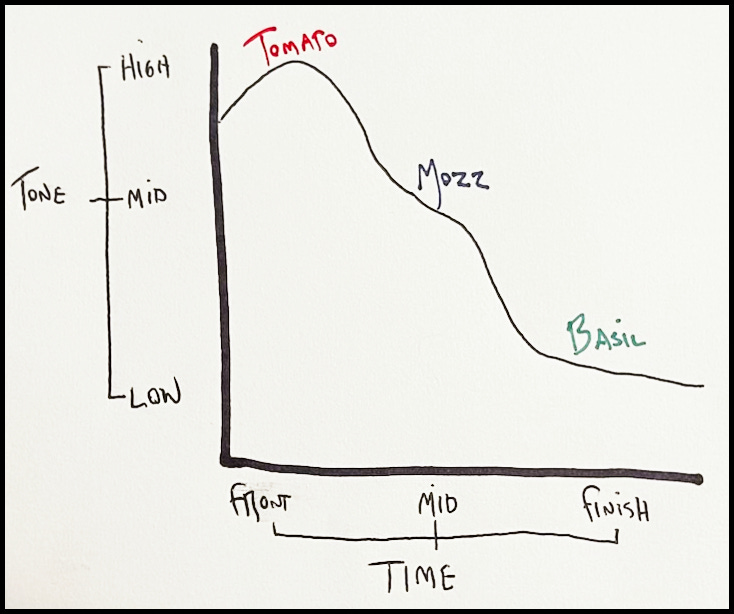

- Has a distinct beginning, middle, and end. Each ingredient plays a role, and you taste everything — not as a shotgun blast of complementary flavors, but as an elegant unfolding on the palate.

- Spans the palate across high tones, mid tones, and low tones. If it were all high notes — lemon zest, St. Germain, and fresh raspberries, say — it would be good but not great, because it would just hang out up there, on the tip of your tongue. Similarly vanilla, Cynar, and coffee: delicious but redundant, because they’re all low tones. Great drinks, for me, travel across the tonal flavor spectrum.

- The Flavors work. Obviously. No amount of clarity or tonal fascination can save it if the flavors don’t work together.

There are exceptions to this — some great drinks aren’t #2, and some aren’t even #1, though they all are #3 — but for the most part, this is what I’m looking for when I’m making or drinking cocktails. Below, I will explain a little more.

Mercy Rule: If you’re just here for the advertised “favorite Manhattan recipe” and don’t have five minutes for the why of it all, just click here.

Good Drinks vs. Great Drinks

Good drinks are easy. Anyone can make a good drink. Grab the Flavor Bible, pick any two ingredients that go together — blackberries and sage, say, or peaches and thyme — and put them together with a spirit and then sweet/sour balance, and voilà. You did it. Amazing.

Great drinks are a different thing entirely. Great drinks aren’t just about the flavors working, they’re about the unique flavor signature of each particular ingredient. To explain:

The problem with cocktails is that unlike chefs, we don’t have texture to play with. Take a caprese salad: Basil, tomato, and mozzarella, combined to form one of the best things on earth. The textures mean that even though you get all three on the same bite, they hit your palate at different times — the tomato is up front, sweet and acidic, and you taste its juiciness before you even start chewing. Then comes the creamy mozzarella, rich and resonant, occupying the middle and tempering the sweetness of the tomato. Then finally, after a few chews, basil begins to really express itself, from what was just a fragrance to a musky and robust herbaceousness that lingers on the finish.

High, middle, low. Beginning, middle, end. The Caprese is a great dish.

Now imagine that someone put those three in a blender and invited you to drink it with a straw. Still good? It’s the same flavors, right? Ignoring the fact that you’d be dealing with a psychopath, perhaps you take my point: remove texture from the equation and suddenly everything hits all at once, and while the flavors are still fine, you lose something essential of the dish.

Now consider a cocktail. Cocktails are homogeneous — every sip is exactly the same, and you taste every ingredient all at once. So if you want a drink with a distinct beginning, middle, and end — and what’s more, if you want it to have high notes, mid notes and low notes — you need to do it with the inherent character of the ingredients themselves. This is why great drinks are hard. Liquids react to each other in interesting and sometimes unpredictable ways, so to make something great, you need to either (1) know your ingredients preternaturally well, or (2) do a ton of trial and error.

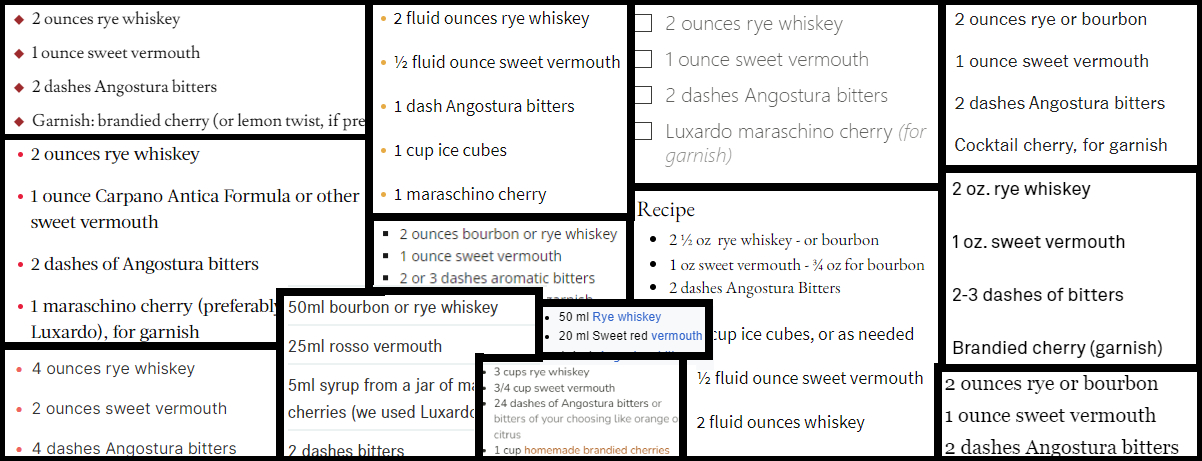

The Problem with Most Recipes

This is why it drives me nuts to see cocktail recipes that don’t mention a style or a producer, and will be like: “use 2oz rye.”

I’m sorry, “RYE?”

It’s all at least 51% rye and it’s all aged in oak, but beyond that, there are wild differences between the bottles. By “rye” do you mean punchy and full of corn like Rittenhouse? Or soft and green like Templeton? Or also soft and green but also heavily filtered like Dickel? Or fruity and a bit hollow like Old Overholt? Or chocolaty and deep with 100% malted rye like Old Potrero? Or aggressive and intense like Pikesville? Is the sweet rum barrel finish of Angel’s Envy OK? Any help on any of this? Nope. Just “rye.”

Some cocktails, like the Whiskey Sour or Old Fashioned, are so basic and protean as to taste good with everything, but they’re the minority. When vermouth and juices and liqueurs start getting involved, just calling for a certain measure of “rye” is like giving up on the idea of greatness before you even start.

This is why I tend to get prescriptive about brands. Not because I take any money from them (I don’t), but because a cocktail recipe is like a biometric safe, and to make a great drink — what I’m always looking for, in accordance to those three goals at top — you need the specific fingerprint of a specific bottle or category to unlock it.

The Manhattan

My go-to Manhattan is for me the most dynamic, the one which takes me on the biggest and most satisfying flavor rollercoaster.

That being said, it’s important to note: I’m not here to say there’s one “best” version of each drink. There are, in fact, a bunch of truly great Manhattans, more than a few tall peaks on that particular flavor landscape. I’ve found three so far, and I know there are many, many more I’ve not yet discovered.

I’m going to show you the one I tend to reach for most often because of my particular tastes, but I’m not saying it’s better than other great Manhattans. What I’m saying is that all the great Manhattans are better than the ones that are merely good.

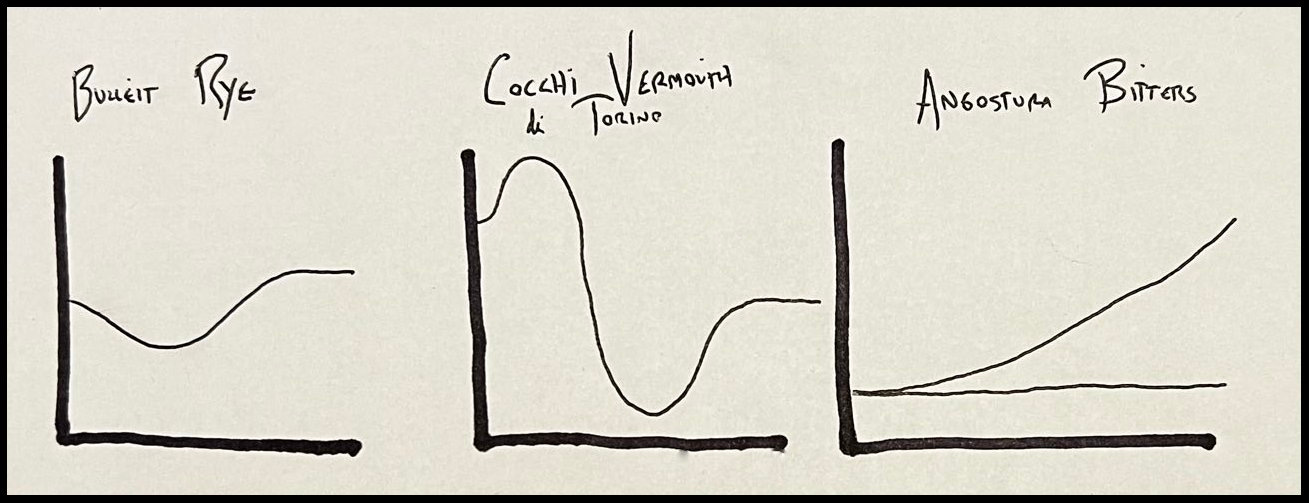

The one I tend to make the most is Bulleit Rye, Cocchi Vermouth di Torino, and Angostura Bitters. Every liquid ingredient has its own flavor curve, where and when on the palate it expresses itself. I think of their flavors like this:

Bulleit Rye: Starts very quiet, with a gentle light grain sweetness, goes a touch low in the midpalate, and then finishes higher with textured oak and the rye’s spice.

Cocchi Vermouth di Torino: Sweet and high fruity up front, then the midpalate swings dramatically down with a low vanilla hum, then it comes up to the rest of the herbs and a lightly sweet, light bitter finish.

Angostura Bitters: There’s a low bitter floor that persists the whole way, but it also has non-bitter flavor notes, which rise in baking spices and citrus through the palate. This complexity is one of the reasons Angostura is perpetually better than its competitors.

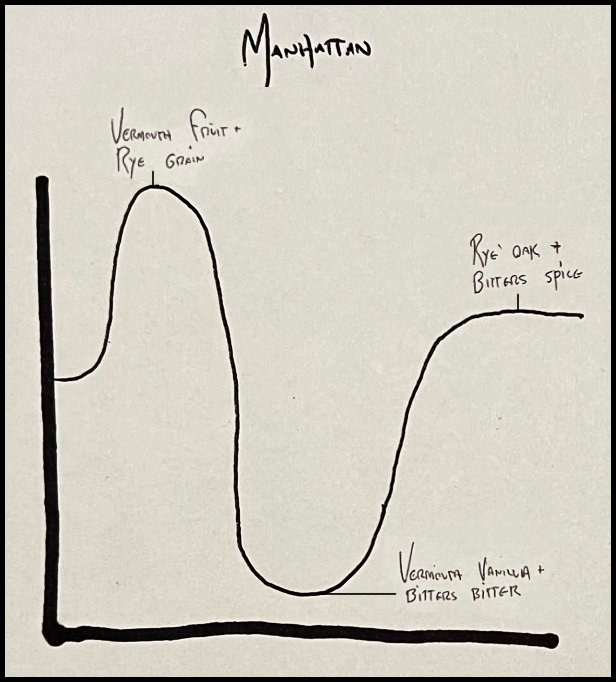

The Manhattan, put together:

There’s just so much movement in this version. It goes high to low and then mid-high again, and each peeling off one-by-one. Remember that the liquid is completely mixed, and each sip is exactly the same, so when you can find ingredients that give you this kind of ride just through the interactions of their innate personalities, you, my friend, have found a great drink.

My favorite Manhattan (so far):

- 2.25oz Bulleit Rye

- 1oz Cocchi Vermouth di Torino

- 3 dashes of Angostura Bitters

Chill a coupe or cocktail glass. Then add all the ingredients to a chilled mixing glass with ice, and stir for 15-20 seconds (on decent ice) or 10-15 seconds (on shitty ice). Taste before you strain — you’re looking for the flavors to be clear and articulate. If the ingredients are all trying to speak at the same time, stir for 5 more seconds, but try not to overdilute. The Manhattan is frustratingly easy to under- or over-dilute. It’s not that hard, just a little annoying in the beginning. Once you know what you’re looking for, you can hit it every time.

Two Parting Questions:

- What did you think about this? Do the visuals make sense to you? Do you think about tasting some other way?

- Do you have a favorite Manhattan? If so, DM me, or leave it as a comment. I’d love to try it out. The work is never over.

I drink Manhattans because they’re never bad (at least in my house). Right now I’m using New Riff Bonded with Carpano Classico although this one is better with Bitter Truth Jerry Thomas Decanter Bitters. I actually like Manhattan variations with Tom Macy’s “Rhapsody in Rye” leading the pack and Difford’s “Ragtime” going a little further afield.

sorry I’m so late to the party. My everyday Manhattan recipe is three parts Bulleit rye, one part Antica Carpano sweet vermouth, several dashes Peychauds bitters. I increase the rye content b/c the vermouth is more assertive than most.