Note: For brevity’s sake, I’m going to breeze over some of the finer points of distillation, as I’ve already written about them in part 1. For a more thorough breakdown of the bourbon process from grain to bottle, click here, or just type your question in the comments.

The Facts:

Distillery: Heaven Hill Distilleries, Inc.

Location: Louisville, Kentucky and Bardstown, Kentucky

Owned By: Privately owned by the Shapira Family.

Major Products produced: Elijah Craig; Evan Williams; Rittenhouse Rye; Bernheim; Parker’s Heritage; Fighting Cock; Old Fitzgerald; Henry McKenna

Origin: Since 1935

The Tour:

Everybody’s owned by somebody. For all their talk about heritage and old bricks and father’s fathers, pretty much every major bourbon distillery is now owned by some massive, international corporation: Wild Turkey by the Italian Gruppo Campari, Buffalo Trace and 1792 Barton by Louisiana’s Sazerac, Four Roses by Kirin in Japan, etc., etc. So when I was doing research on Heaven Hill and found that they are “America’s Largest Independent Family Owned and Operated Distilled Spirits Company,” I was excited to see how that might change the experience.

Heaven Hill are also the only people who offer an in-depth tour to the general public, a $25, 3 hour “behind the scenes” experience. As someone who flew to Kentucky for semi-professional reasons, I was sincerely excited about this as well. Three hours! Family owned! We built the whole day around our Heaven Hill appointment, as I assumed it would be the most interesting, the most hands-on and educational.

As it turns out, it was none of those things. Which I’ll explain, but first, a quick aside about the alcohol business: warehouses can hold about 20,000 53 gallon barrels, which due to evaporation have various levels of fullness. But even if the warehouses were only half full of barrels, and each barrel was only half full of spirit, that’s still 2.5 million pounds of insanely flammable liquid. Fires happen. And when they do, they’re not minor.

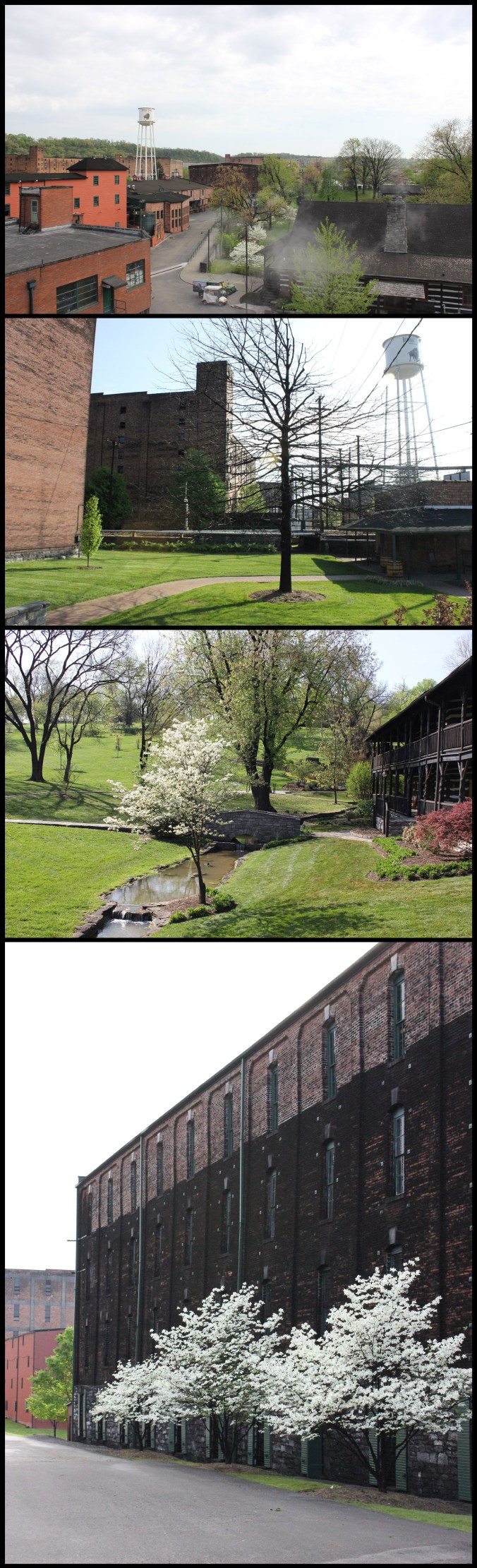

So while Heaven Hill is based in Bardstown, KY, it has been fermented and distilled in Louisville since 1996, ever since their Bardstown Plant was ravaged by fire and burned to the ground.

What does that mean for your average bourbon tourist? It means that if you do a three-hour tour, you get a three-hour tour of a dumping & bottling plant. We learned almost nothing about bourbon; instead, we learned about the bourbon industry, the nuts and bolts of how such a massive production can be achieved, which is interesting in the way that patent law is interesting. It is conceptually interesting.

Actually immersing oneself in it for several hours, however, is a slightly different story.

MASH, FERMENTATION, and DISTILLATION

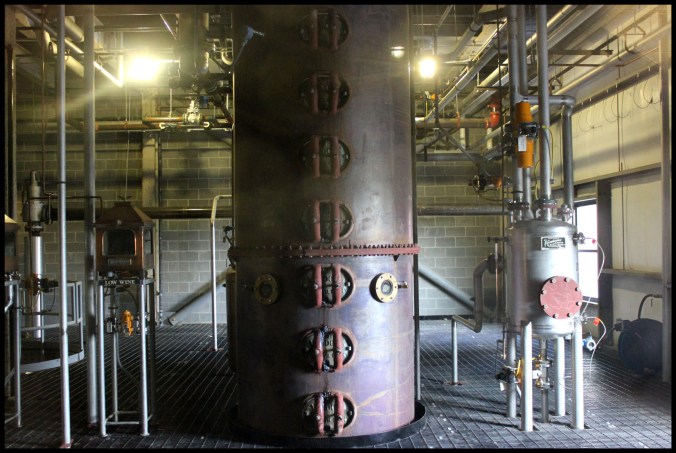

We were told that they use 78% corn and 11% each of rye and barley, but it may be 75/10/15 according to a strange little case off the factory floor (pictured above). I know it’s fermented in stainless steel, then it’s distilled via column to 138 proof before being trucked to Bardstown for barreling. And that is everything I know about production.

AGING:

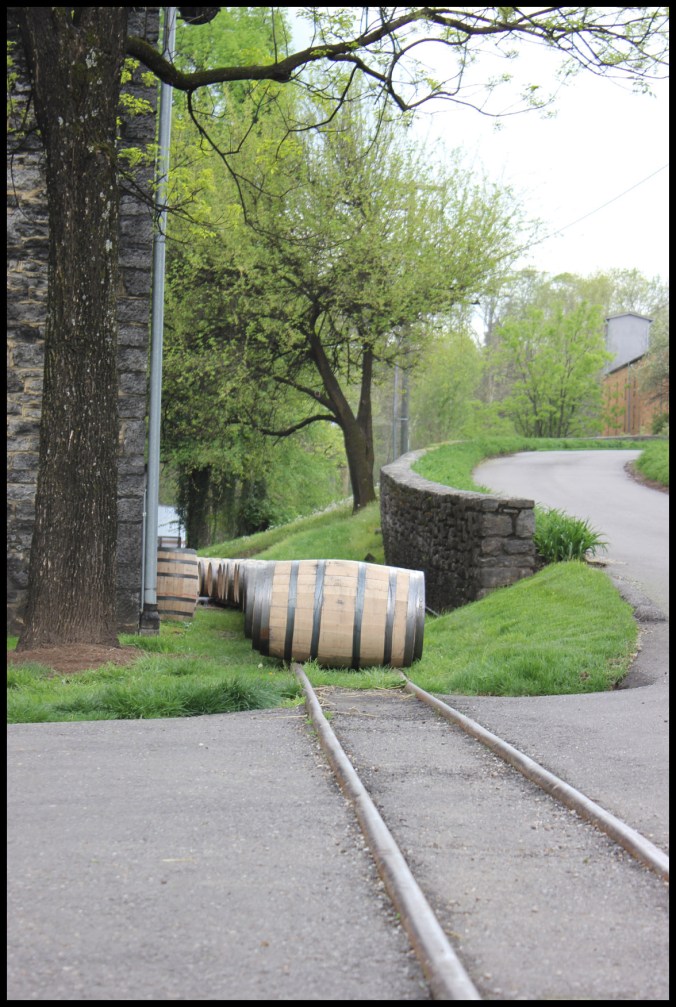

It may be “family owned,” but it’s not like the tour goes through someone’s kitchen. Heaven Hill is, in fact, the biggest distillery of the six we saw, and the second biggest in the state. They have a standing inventory of some 800,000 barrels and are distilling about 15 million gallons each year (or about 280,000 new barrels), which they keep in 49 aging warehouses that stand like monuments out on the open plains.

BARRELING:

This was one cool thing we didn’t see anywhere else: how exactly does the whiskey get into barrel? Behold:

A giant series of tubes sucks the new spirit out of its holding tanks and impregnates the charred oak barrels with it, and then another machine taps the cork — or “bung” (seriously) — securely in. They filled 283,000 barrels in this manner last year, which is a whole lot of barrels. If these machines had been running 24 hours a day (they’re not), that would be more than one barrel every two minutes, nonstop for a year. Which, again, is a whole lot of barrels.

These giant tubes are a relatively new system — apparently, this room used to employ eight people, and the new machines have cut that to three. Our tour guide seemed strangely proud of this fact.

TESTING:

With such an expansive stock, they need to make sure nothing goes wrong. So they have a full-time laboratory on-site, where every single batch gets tested. Each batch (truck-full of barrels) is about 8000-9000 gallons, and before bottled, each one is rigorously tested for proof, chemical levels, etc. They answer directly to the Alcohol, Tobacco and Trade Bureau (TTB), which as it turns out is the ATF’s successor. The ATF doesn’t exist anymore. No more ATF. Huh.

With such an expansive stock, they need to make sure nothing goes wrong. So they have a full-time laboratory on-site, where every single batch gets tested. Each batch (truck-full of barrels) is about 8000-9000 gallons, and before bottled, each one is rigorously tested for proof, chemical levels, etc. They answer directly to the Alcohol, Tobacco and Trade Bureau (TTB), which as it turns out is the ATF’s successor. The ATF doesn’t exist anymore. No more ATF. Huh.

LABELS:

We were taken to a room the size of a high-school gymnasium and shown the label binders, where they keep master copies of every label for every size of every bottle they make. All 1400 of them. The actual labels to be fed into the hungry machines are stacked 15 feet high on row after row of industrial shelving.

The label room is representative of the larger tour for three main reasons: (1) it had nothing whatsoever to do with what’s inside the bottle, (2) it’s a side of the whole business that we didn’t see anywhere else, and (3) it was oppressively fucking dull.

BOTTLING PLANT:

Their bottling operation is truly enormous. There is an entire capacious warehouse where they just make and store nips, the little 50ml airplane bottles. They were churning out pink-limonade flavored vodka ones while we were there. There are a series of 25-foot tall hydraulic claws to stack pallets, in a room designated just to deal with empty bottles waiting to be filled. On the belts, they’ve got high-speed digital cameras which quality-check the bottles for fullness, label straightness, etc, that can scan 400 bottles per minute for 12 different quality points, automatically discarding flawed ones. It is loud and busy and hopelessly complex, thousands of things going in all different directions of 3-dimensional space, and going there very quickly.

The overall impression is of an operation so big, no one could possibly know everything about it. We never did get to find out of that was true, because after more than an hour of our guide pointing proudly at machinery, it was time for a drink.

TASTING:

We tried two single barrel offerings, The Evan Williams 12 and the Elijah Craig 18. I will say this about Heaven Hill: for all their size and relative tedium, they can make a good whiskey.

- The Evan Williams 12-year was recently inducted as one of now eight total spirits in F. Paul Pecault’s “Hall of Fame,” which is a not-insignificant honor. It is delicious — bright and almost fruity, very full bodied with oak and age mixing perfectly, and at $25 is a hell of a deal.

- The Elijah Craig is a bit less complex, but it’s gift is age: there’s something distinctly inimitable about long-aged bourbon. It gets a full richness to the oak that can’t be simulated by aging in smaller barrels or under more extreme conditions, and the Elijah Craig 18 hits that note hard. That’s more or less all there is to it, actually… which is an overstatement, but not a big one. It’s been recently discontinued but is still around, and at $40/bottle, it’s the cheapest fix for lovers of old whiskey.

- Rittenhouse Rye: we didn’t taste the Rittenhouse that day, but this is the only other product out of Heaven Hill that I have extensive experience with, and note it here because it is noteworthy. Rittenhouse is 100 proof, big and spicy, and at $20 is a steal. I personally don’t like to sip it, but it’s my go-to for Manhattans, even compared to bottles three times its price. A marvelous cocktail rye.