INTRODUCTION to the OLD FASHIONED WHISKEY COCKTAIL (PART I)

I remember the exact moment when I learned how to drink.

I was a Jack & Coke kid all through college. Tequila shots, Jameson rocks, Vodka Redbull. I’d get the cheapest single malt on the menu for special occasions. I learned to drink straight whiskey, but mostly because I wanted to be the type of guy who could drink straight whiskey. I once spent an entire night drinking Jäger bombs (never again), and was elated when I discovered that the dueling piano bar sold Long Island Ice Teas by the bucket. I looked down on Miller Light in favor of Bud Light. I believed in the idea of “ultra-premium vodka.” In short, I knew nothing.

It wasn’t until I left Los Angeles for Boston that I had a conversion experience. Winter hit quickly for those of us who’d just spent four years in southern California, and it was already brisk in early October when my sister took me out to the neighborhood bar, Green Street Grille, for a drink. Our bartender was Misty Kalkofan – Misty, half-sleeve tattoo, bellowing infectious laugh, with a M.A. from Harvard Divinity School and one of the best bartenders in the city.

I ask for a Jack and coke, but Misty tells me they don’t have Jack. I ask her what she has. She asks me what I like.

“Whiskey.”

“Spirit forward or more drinkable?” she asks. I revert to my college mentality, one of cool and uncool, and order straight whiskey as if the syllables themselves are laced with pheromones.

“Jameson,” I say, “Neat.”

Bartenders deal with this chest-puffing horseshit all day long, and in hindsight, Misty treated me with a truly profound kindness.

“Have you ever had an Old Fashioned?”

This was pre-Mad Men, though I had heard of it but never tried one, and acquiesced. A couple dashes of those weird bitters things, a sugar cube, orange peel and rye whiskey, and that was it for me. I was sold on cocktails forever. I had never tasted anything like it.

I don’t remember the drink I had before that Old Fashioned, but whatever it was, it was the last time I’d take a drink without thinking about it. Without weighing it’s taste, complexity, and balance. I plainly didn’t realize drinks could be that good.

It’s been more than four years since then. It’s what turned drinks from object to subject, and what changed bartending from a job to a career. It is the drink I have the most respect for, one of the pantheon of cocktails on which, when ordered on the 4-deep, cash waving insanity of a busy Saturday night, I will never cut corners. It is what I order to test knowledge or skill of a new bar or bartender. The Old Fashioned – short for Old Fashioned Whiskey Cocktail – was, and remains, the best drink I’ve ever had.

WHAT IS IT, and WHY IS IT SO DAMN GOOD? (PART II)

When Humphery Bogart died and went to Whiskey Heaven, the bartender greeted him warmly, and slipped an Old Fashioned into his hand.

It is not a classic cocktail, it is the classic cocktail. To explain:

While the term “cocktail” might today refer as equally to a Sazerac as an Appletini, in the beginning, everything had an exact definition. There were Slings (spirit, sugar, and cold water), Toddies (spirit, sugar, and warm water), various citrus Punches and such, but no cocktail. It wouldn’t be until 1806 that the “cock-tail” was defined in print*. Then, it was “spirits of any kind, sugar, water, and bitters.” Those four ingredients made a cocktail. Anything else, tasty as it may be, wasn’t a cocktail.

But over the next 75 years, people kept tweaking the cocktail, hanging ornaments on it. There was the “fancy cocktail,” with curacao. Then the “improved cocktail,” with maraschino liqueur and absinthe. Then “what if we throw some Chartreuse in there?” and “here’s a float of red wine,” and people started using pineapple sticks and raspberry syrup and muddling in fruit slices – what would be referred to, later, as “the garbage.” It’s an enormously malleable template, and can be mangled as many different ways as there are bottles on the back bar… and while it was likely all delicious, it was not a cocktail as it was originally defined.

So when a reference to “old-fashioned cocktails” appears in print in The Chicago Tribune in 1880, it’s not that someone invented a drink that felt quaint and homey, and named it an Old Fashioned. It was a curmudgeon with a healthy dose of grump and thirst to go with it, who wanted a cocktail, the kind he used to get. The Old Fashioned kind. The only change he’d accept from the original 1806 cocktail was ice. All else was heresy.

(It’s worth noting that any claim to have “invented” the Old Fashioned is absurd, seeing as it was being made for at least 75 years, as a “cocktail” before it earned its latter name. But extra bullshit points go to the Pendennis Club of Louisville, who maintain their paternity claim even though they opened their doors in 1881, a full year after it first appeared in print.)

As it was, so it is.

The Old Fashioned (Whiskey Cocktail)

2oz. rye whiskey (or bourbon)

2 dashes angostaura bitters,

1 small sugar cube, muddled or ~1/4oz simple syrup (a hair less for the inherently sweeter bourbon)

Add ice and stir briskly for 30 seconds or so. Express oils from a long strip of orange peel, drop peel in drink. Garnish with a maraschino cherry. Drink. Melt.

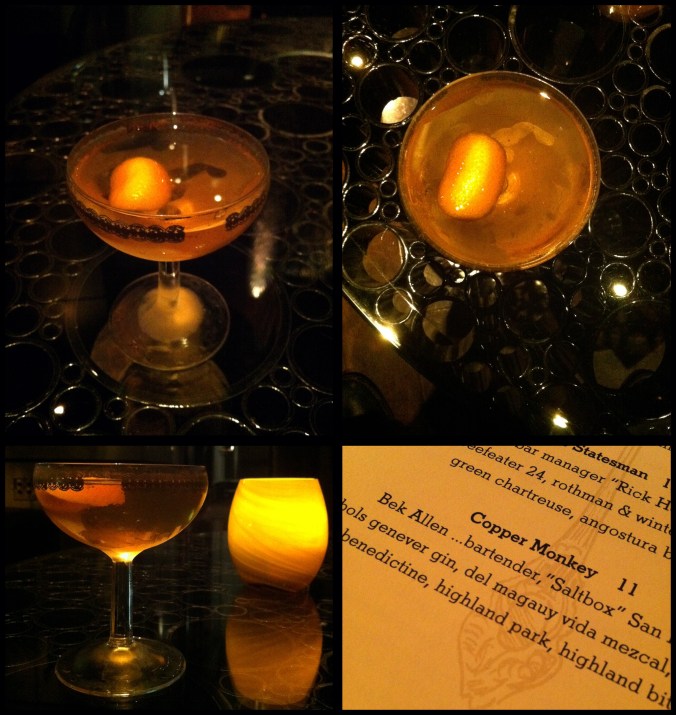

It should look like this: (and I’m sorry for the image quality of these pictures… I took them before this blog existed.)

*Nerd stuff: I have recently seen trustworthy evidence put forth by cocktail historian Jared Brown that “cock-tail” appears in print in 1798, a full eight years earlier than we originally thought. It is, alas, not defined, so the 1806 date remains, at least, not wrong.

OLD FASHIONED in SAN DIEGO (PART III)

There is literally nothing old fashioned about Southern California. In Los Angeles, they throw stones at anything older than 35, and San Diego roughly the same. Things don’t last here. Even Old Town feels new.

So it is with the Old Fashioned. With this drink, there are two rival camps, between whom there can be no peace. To garnish with the fruit, or to muddle it. One of them prefers the nuance and subtlety; orange oils accenting the whiskey, a little sweetness to wake it up, and a little bitterness to add spice and complexity, with minute variations in the choice or quantity of ingredients shifting the focus and balance for myriad incarnations. The other one prefers a swamp of pulpy fruit carcasses that add blunting sweetness, fibrous bits to get caught in your teeth, and a mess of trash in the glass. I won’t say which I am.

The good folks at Craft and Commerce know how to do it. Most of their bartenders, when asked for their favorite version, will use the drier, spicier, slightly more challenging rye whiskey, but the house Old Fashioned is with Bourbon. Buffalo Trace, a little bit of cane sugar syrup, angostaura bitters, stirred with both an orange and lemon peel.

At URBN, where I work, we do the same… it was with a single barrel Elmer T. Lee, until we went through about 100 bottles of it and all but ran out. So we, too use Buffalo Trace. Even though we took it off the menu, we still sell dozens of these things a week, and to all kinds of people. It’s something that gives me faith.

Sadly, some of the even very nice bars are muddling fruit. Kitchen 1540, in Del Mar, is one of the nicest restaurants in the area. They serve “craft cocktails” and yet an order for an Old Fashioned returns a very nice bourbon (he used the Van Winkle 12 year, definitely not their standard) and angostura orange bitters (not my taste, but a respectable choice), but sullied with a mashed cherry and dulled with a two-inch-tall hat of soda water.

And I don’t know where this morbid little voice came from, but drinking Haufbrau lager at the splendidly tacky Keiserhoff, in Ocean Beach, a place without computers where they make everyone dress like beer wenches from the German hinterland, something whispered to me that our 60 year old bartender, a consummate professional with more years of experience than I have years of life, that he might, just might, make a mean old fashioned.

I was wrong.

You have to go to a devoted craft cocktail bar to get it the right way. C’est la vie. Always a good excuse to go, I suppose.